Massimo Beccarello, Associate Professor of Economics of Productive Sectors, Università degli Studi di Milano Bicocca

Professor Beccarello, what are the priorities in rethinking the policies for clean energy supply in the Italian economy within the framework of the EU Climate Law, which was presented in March 2020?

The European Commission, in presenting the Climate Law on the 4th of March 2020 gave a clear sign that it wanted to increase decarbonization targets from 40% to 50/55% by 2030. At the same time there was an official drive of support from 12 European Union Member States (including Italy, France and Spain). The new targets make us consider a renewable source make-up of about 40% of the European energy combination. This transformation means giving an unprecedented boost to the electrification process of the economy and transport. For our cities, the tertiary sector and gradually also the industrial sector this means a change in model with an increasing role of Information and Communications Technology in the production and consumption processes. We will have to manage a change from a centralized electrical production system to a production supply system close to consumer catchment areas. Local Energy Communities will be developed in order to facilitate the self -production of energy. In my opinion, two courses of action have priority:

1.Act quickly on red tape, simplify authorizations in the energy sector with reference to production plants and networks, fostering responsibility of local authorities in relation to the decarbonisation targets;

2. The creation of a new model is complex and it is necessary to operate on the level of information for users/citizens in order to avoid adverse reactions. The consumer of the future will be a prosumer, a protagonist within the smart city and will have to be able to contribute directly to it.

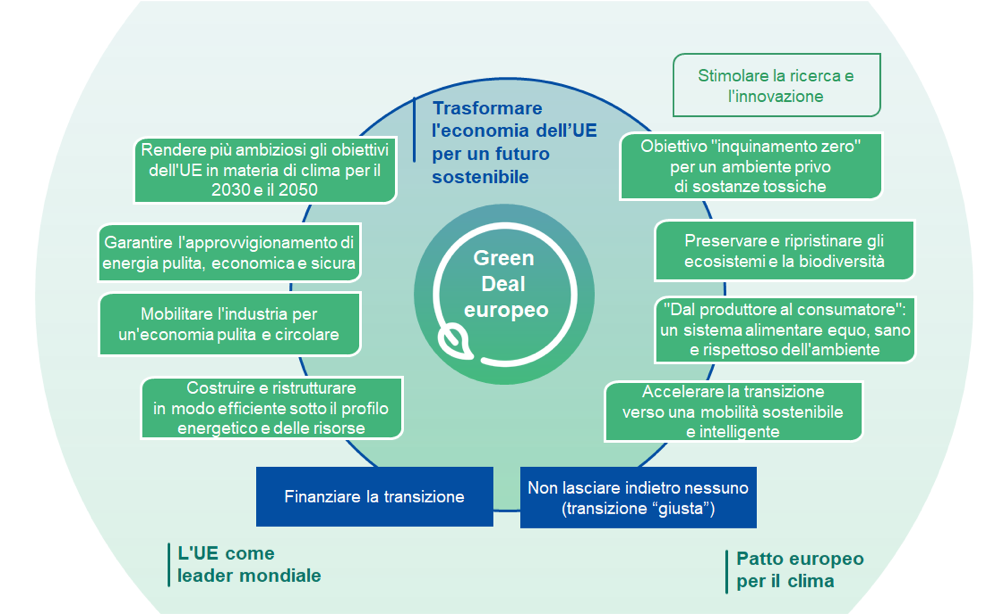

What are the tools and processes to protect, conserve and enhance natural EU assets and to protect the well-being of citizens from the risks and the environmental impacts envisaged by the Green Deal ?

The holistic approach of the Green Deal presented by the Commission, by integrating sustainability policies with those for the circular economy provides for a number of important measures to protect natural capital. The strategy, as set down in the EU plan, operates on a broad scale with environmental guidelines capable of producing knock-on effects on all the natural capital assets (Soil, Subsoil, Water, Climate and Biodiversity). This is particularly relevant for a country like Italy, a country rich, in terms of natural capital and biodiversity. But the sustainability policies of the Green Deal offer a vision of sustainable development with great potential in terms of economic and social impact for a country with outstanding manufacturing know-how and expertise (Italy is second only to Germany in Europe for manufacturing) within a sustainable development outlook. For this reason, environmental targets, which safeguard citizens health must go hand in hand with an economic development outlook to foster growth opportunities and collective well-being.

The European Green Deal was envisaged in a pre-covid era. Is it an adequate tool to achieve its set goal, namely to be the first climate neutral continent? Given your professional experience, including Confindustria, what could be the key for a transformation towards greater sustainability of the Italian industrial system?

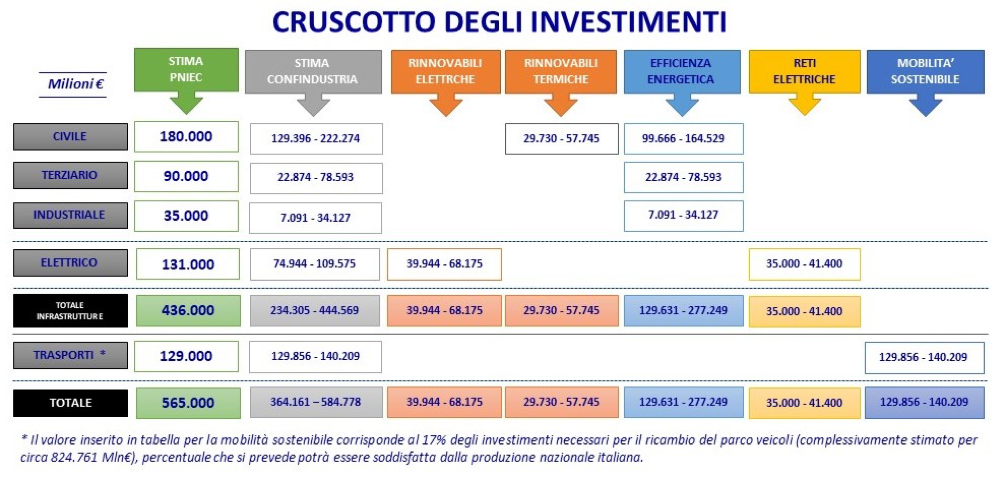

The Green Deal presented in January was a truly unprecedented investment plan in Europe, according to initial estimates, the new decarbonisation targets of between 50 and 55% by 2030 would have entailed additional investments of over 300 billion Euro per year at European level. However if we think about the 2050 perspective of a Carbon Neutral economic system, they seem to fall short. To support these investments the European Commission had hypothesized to mobilize about a third of the resources, that is to say, 1,000 billion Euro between 2021 and 2030, mainly through the European budget, the remaining amount would have to be financed by the private sector.

It is clear that the COVID emergency may have an impact on disposable resources and cause delays, however the effect the project will have on growth must also be considered. According to authoritatively sourced estimates the Green Deal, in the next 10 years, will have a positive effect on GDP consolidating a steady growth of approximately 1.1% and an increase in the employment rate of 0.5%. Italy, too could experience some positive effects on its GDP, up 0.5% per year, according to Confindustria estimates.

Moreover, Italy also holds a leading position in terms of energy efficiency, being the manufacturing country with the lowest energy intensity amongst the 27 member states. In particular, the industrial system has shown interest in the field of sustainability by investing in efficient technologies, such as cogeneration systems, and in processes that reuse and recover waste, transforming it into second materials or raw materials, or use by-products and more sustainable innovative materials reflecting the logic of the circular economy and end of waste strategies.

However, the country lacks a real industrial strategic policy in order to develop an industry of green technologies from renewables through to energy efficiency. On this front, the National Integrated Climate and Energy Plan presented by the Italian government last January should go some way to integrate industrial policies by creating an ecosystem capable of strengthening and fostering industrial development in these technological sectors.

Posters and open letters have recently appeared from national and multinational companies, urging public and private institutions to intervene. In your opinion, what is the likelihood of financing this move towards sustainability in a country/system that risks- according to the latest figures- a drop of 10% in GDP in a single quarter ?

The possibility to finance the change towards sustainability in our country, considering a prospective drop in GDP ranging between 6% and 14% during 2020 because of the healthcare emergency, will come from the ability to redirect the resources necessary to kick start the economy in a sustainable way, that is to say the connection between the covid emergency resources and the green economy ones. It is not only an Italian problem, it is a European one.

Nonetheless, I believe the recent important dynamic activity of finance, starting with the main international investors, which has made sustainability the central axis, not only in name, of future investment policies should not be overlooked. In addition to this, there is the new EU regulation on sustainable finance, which indicates the general reference criteria for the financial instruments of sustainable investments. The new approach to sustainable finance actually marks a point of no return that may compensate for lower public finance resources today rightly addressed to emrgency measures. This however, is also the reason why in this phase, however complex, we must think about the strategy for the development of the new green economy, valorizing the experise of Italian research and creating simplified conditions for a new phase of industrial development.

Finally, we must also consider the idea that lower public finance resources represent a unique opportunity to review the incentive/financing systems that interplay with the energy sector and the circular economy. Let us try to think about taxation on energy and parafiscal levies . Overall, on an annual basis, according to the data from the Ministry of Finance, taxation on energy amounts to over 47 billion euro a year, while the only parafiscal levy in the electricity sector and the revenues from the Emission Trading Scheme amount to approximately 16 billion euro. That is a significant amount of over 60 billion euro. If we try comparing this data to the estimated government targets to 2030, equal to 50 billion euro a year, we can see then that the resources are actually available. By proposing to revise the energy tax regulation Europe recommends taxing energy products on the basis of their carbon content and allocating the resources to decarbonisation policies.